Russia and the Western Far Right

Russia and the Western Far Right

Anton Shekhovtsov

Routledge, Londres et New York, 2018, 262 p.

A review by Galia Ackerman

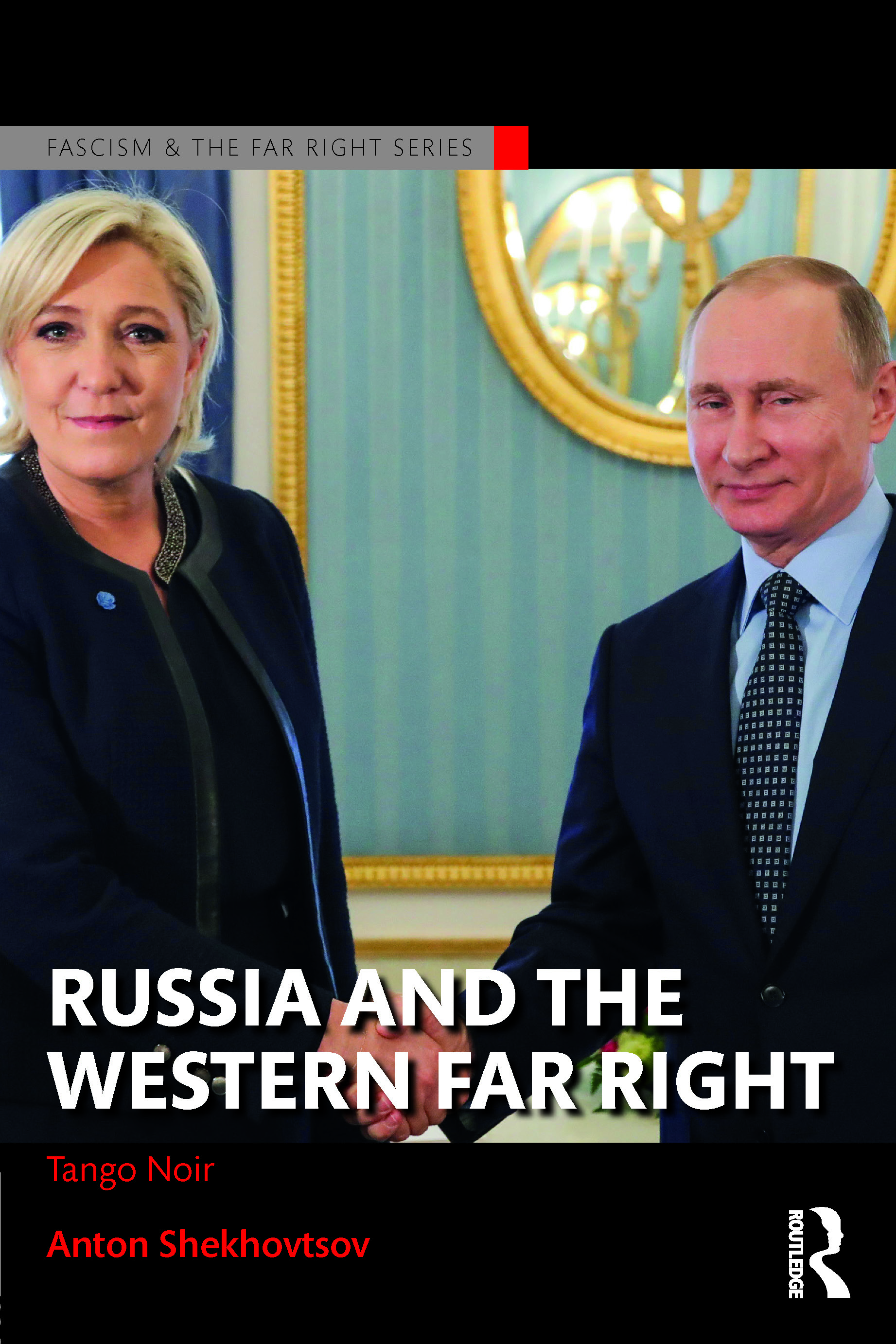

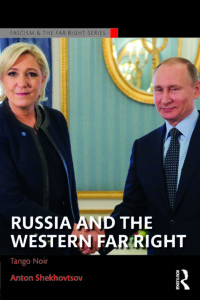

Anton Shekhovtsov est un politologue ukrainien spécialisé dans l’étude des mouvances d’extrême droite en Europe et, en particulier, de leurs liens avec la Russie. Son dernier livre affiche en couverture une photo de Marine Le Pen et de Vladimir Poutine se serrant la main avec un grand sourire. D’entrée de jeu, on comprend qu’une entente cordiale règne entre le Kremlin et le Front national (ainsi qu’une multitude d’autres partis européens d’extrême droite).

Anton Shekhovtsov est un politologue ukrainien spécialisé dans l’étude des mouvances d’extrême droite en Europe et, en particulier, de leurs liens avec la Russie. Son dernier livre affiche en couverture une photo de Marine Le Pen et de Vladimir Poutine se serrant la main avec un grand sourire. D’entrée de jeu, on comprend qu’une entente cordiale règne entre le Kremlin et le Front national (ainsi qu’une multitude d’autres partis européens d’extrême droite).

Une telle proximité, détaillée tout au long de cet essai stimulant dont on espère qu’il sera rapidement traduit en français, s’explique par un ensemble de considérations aussi bien domestiques qu’internationales. Pour résumer, l’extrême droite européenne comme le régime poutinien visent, en se liant, à remodeler à leur avantage un environnement hostile.

La connexion ne date pas de l’arrivée de l’ancien agent du FSB au pouvoir, en 2000. Mais, au départ, son régime, quoique déjà corrompu et autoritaire, entretient des rapports plutôt corrects avec la communauté internationale et ne se préoccupe guère des forces extrémistes actives dans les pays occidentaux. En revanche, à partir de 2003, Poutine se sent menacé par les révolutions dites « de couleur » qui surviennent en Géorgie, puis en Ukraine et au Kirghizstan. Ces protestations de rue se soldent, chaque fois, par le renversement des régimes corrompus en place dans les pays en question. À Moscou, on est persuadé que derrière ces mouvements populaires se trouve l’ennemi historique, les États-Unis, déterminés à déstabiliser le voisinage immédiat de la Russie et, de cette façon, à contribuer, un jour, au renversement du régime russe. Ces idées paranoïaques contribuent, explique Shekhovtsov, à l’ouverture graduelle des élites moscovites en direction des politiciens européens d’extrême droite, connus pour leur détestation de Washington. Ceux-ci, de leur côté, essayaient depuis longtemps déjà de courtiser le Kremlin qui incarne à leurs yeux une alternative crédible à l’atlantisme, réel ou supposé, des élites européennes. On le voit : l’anti-américanisme que les deux parties ont en partage constitue un premier facteur de rapprochement. […]

A central accusation in the uproar over “Russian influence” holds that Moscow is covertly in cahoots with the American alt-right, supplying the movement with fake news, memes, and social media talking points. The evidence for this tends to be more speculative than solid, but the general question of post-Soviet Russia’s cooperation with Western nationalist and racialist groups is certainly salient.

A central accusation in the uproar over “Russian influence” holds that Moscow is covertly in cahoots with the American alt-right, supplying the movement with fake news, memes, and social media talking points. The evidence for this tends to be more speculative than solid, but the general question of post-Soviet Russia’s cooperation with Western nationalist and racialist groups is certainly salient.