Introduction*

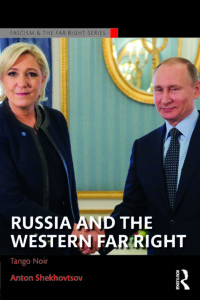

In the recent few years, there has been a growing concern in the West about the convergence or, at least, marriage of convenience between Vladimir Putin’s Russia and far-right forces in the West, most notably in Europe. Indeed, we have witnessed the increasing number of far-right politicians’ statements praising Putin’s Russia and contacts between the Western far right and Russian officials and other actors.

Concerns about these developments seem to be even more pronounced given the present condition of the West characterised – among many other ills – by the threat of terrorist attacks, migration and refugee crises, austerity policies, the Eurozone crisis and perceived lack of effective leadership. Moscow’s apparent cooperation with the far right, which blame liberal-democratic governments for the West’s woes, is often interpreted, especially in the Western mainstream media, as an attempt to weaken the West even further and undermine liberal democracy internationally. For example, an article in Foreign Policy argues that ‘Russian support of the far right in Europe has [to do] with [Putin’s] desire to destabilize European governments, prevent EU expansion, and help bring to power European governments that are friendly to Russia’. An article in The Economist presumes that the rise of the far right ‘is more likely to influence national politics and to push governments into more Eurosceptic positions’ and this will make it harder ‘for the Europeans to come up with a firm and united response to Mr Putin’s military challenge to the post-war order in Europe’.

Are these fears and anxieties regarding Moscow’s intentions or expectations justified? Does Putin’s Russia – by cooperating with illiberal and isolationist politicians and activists in the West – pursue policies seeking to undermine Western liberal-democratic governments and weaken Western unity? At the same time, why has Putin’s Russia recently become a focal point for many Western far-right parties and organisations and what do they expect from cooperation with Russia? These questions constitute some of the main issues addressed in this book.

However, they cannot be pursued out of a more general context. Thus, before I proceed with a discussion of the existing literature on the subject and outline the main hypotheses and structure of the book, I will provide this general context by giving a brief overview of Russia’s contemporary relations with the West, on the one hand, and surveying the contemporary far-right milieu, on the other, as well as explaining major concepts and terms used throughout the book.

Re-emergence of the Russian challenge

After the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, the West welcomed Russia as a democratising state and embraced its apparent desire to integrate into the Western markets and political institutions. As a legal successor of the Soviet Union, post-Soviet Russia assumed the Union’s seat in the United Nations (UN), including the permanent seat in the UN Security Council, thus retaining the powerful instrument of exerting international influence. The European Economic Community and, later, the European Union (EU) became Russia’s main trading partner; Russia joined the Council of Europe (CoE) in 1996 and was admitted into the Group of Seven (better known as G7), the elite club of major industrialised countries that, consequently, became G8 in 1997. The same year, the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council was created and then replaced, in 2002, by the NATO-Russia Council, ‘a mechanism for consultation, consensus building, cooperation, joint decision and joint action, in which the individual NATO member states and Russia work as equal partners on a wide spectrum of security issues of common interest’. It appeared that – recalling the intellectual movements in the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century – the Russian Westernisers (zapadniki) eventually won over the Slavophiles (slavophily), the adherents of Russia’s authoritarian ‘special path’.

In reality, however, the relations between the West and Russia already in the 1990s were a cynical case of (self-)deception. While presenting itself as a striving liberal democracy, Russia occupied part of post-Soviet Moldova and backed the creation of an unrecognised state of Transnistria in 1992. In 1994–1996, Russian armed forces ruthlessly suppressed the Chechen separatists during the First Chechen War. None of these developments hampered Russia’s joining the CoE. Perhaps predictably, Russia has failed to honour some of the most important obligations and commitments that it undertook when it joined the CoE: it has not ratified Protocol No. 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights concerning the abolition of the death penalty; neither has Russia denounced the concept of ‘near abroad’ that effectively identified the other former Soviet republics as Russia’s zone of special influence; nor has Russia withdrawn its troops from Transnistria although it officially agreed to do it first by 1998 and, later, by the end of 2002. The CoE would repeatedly reprimand the Russian authorities over the non-fulfilment of their obligations and commitments, but Russia ignored the appeals and went unpunished.

Western liberal progressivists assumed that it was necessary to be patient with Russia: its pace of reforms might not be as fast as that of Poland or Hungary, but Russia’s integration into the capitalist market and international institutions would put the country firmly on the track democratising political reforms. This assumption failed miserably.

In the 1990s, Russia’s transition from a socialist planned economy to a capitalist market economy turned into a catastrophe for the Russian society. As David Satter put it, the course of reforms in Russia was shaped by a set of attitudes that included ‘social darwinism, economic determinism and a tolerant attitude toward crime’. While the population became impoverished, money was concentrated ‘in the hands of gangsters, corrupt former members of the Soviet nomenklatura, and veterans of the underground economy. Resources were controlled by government officials’. The Russian state itself turned into what can – in an exaggerated form – be called ‘a mafia state’. Ironically, the first noteworthy assessment of Russia as a mafia state originated from Russia’s first president Boris Yeltsin himself: in 1994, he publicly described his own country as the ‘biggest mafia state in the world’ and the ‘superpower of crime’. Behind these sensationalist terms was the fact that [int he words of Serguei Cheloukhine and Maria R. Haberfeld]:

Corruption in Russia has penetrated the political, economic, judicial and social systems so thoroughly that has ceased to be a deviation from the norm and has become the norm itself. By pursuing poorly thought-out actions during its transition to a market economy [in the 1990s], the state became a generator of crime; in other words, the authorities became criminal-based institutions generating a social behaviour.

All-permeating corruption became a major foundation of the ‘virtuality’ of Russia as a democratic state. This ‘virtuality’ was further advanced by the development of a new class of people who helped the ruling elites run the country, namely political technologists, ‘ultra-cynical political manipulators who created a fake democracy because Yeltsin couldn’t build a real one, and who distracted the population with carefully scripted drama because the energy wealth had temporarily stopped flowing’. In a sense, political technology in Yeltsin’s Russia became a substitute for efficient political institutions, just as corruption was a substitute for working economic institutions that Yeltsin failed to build after the demise of the Soviet Union.

The West played a detrimental role in this process: not only did Western capitals ignore the negative developments in Russia, ‘the Western community [also] allowed the Russian elite to turn its banks and business structures into machines for laundering Russian dirty money. And the West’s political and business circles understood perfectly what was going on’.

Western governments did heavily criticise the Russian authorities over their actions during the Second Chechen War that started in 1999. There were strong statements and speculations about Western economic sanctions against Russia. US President Bill Clinton threatened that Russia would ‘pay a heavy price’ for its actions, while UK Foreign Secretary Robin Cook compared Russia’s tactics in Chechnya to those of Yugoslavia’s President Slobodan Milošević in Kosovo – this was a menacing statement considering that NATO allies had bombed Milošević’s Yugoslavia for the persecution of the Albanian population in Kosovo. However, no matter how strong the words of Western leaders were, none of their statements was accompanied by any policy initiative. The head of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) acknowledged there was little that the organisation could do ‘beyond attempting to put moral pressure on Moscow’. The Parliamentary Assembly of the CoE (PACE) suspended Russia in 2000 because of the human rights violations in Chechnya, but reinstated it within less than a year, despite the fact that Russia continued to violate human rights in the insurgent region.

After Putin replaced Yeltsin as Russian president, the situation gradually worsened. Not only did Russia maintain military presence in Moldova’s Transnistria in violation of its commitments and invade Georgia in 2008 without any consequences from the West, but Putin’s regime became also increasingly right-wing, authoritarian, patrimonial and anti-Western.

To thwart the attempts of some countries in the ‘near abroad’, in particular Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, to move closer to the West, Moscow drew upon the Soviet experience of so-called active measures (aktivnye meropriyatiya). According to one Soviet top-secret counterintelligence dictionary, active measures are ‘actions of counterintelligence that allow it to gain an insight into an enemy’s intentions, forewarn his undesirable moves, mislead the enemy, take the lead from him, disrupt his subversive actions’. Active measures are implemented through ‘actions aimed at creating agent positions in the enemy camp and its environment, playing operational games with the enemy directed at disinforming, discrediting and corrupting enemy forces’. Oleg Kalugin, former Major General of the Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti (Committee for State Security, KGB), described active measures as ‘the heart and soul of the Soviet intelligence’:

Not intelligence collection, but subversion: active measures to weaken the West, to drive wedges in the Western community alliances of all sorts, particularly NATO, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people of Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs. To make America more vulnerable to the anger and distrust of other peoples.

From a practical perspective, according to Richard Shultz and Roy Godson, active measures could be ‘conducted overtly through officially sponsored foreign propaganda channels, diplomatic relations and cultural diplomacy’, while covert political techniques included ‘the use of covert propaganda, oral and written disinformation, agents of influence, clandestine radios, and international front organizations’. Scientific progress and subsequent technological innovations since the Cold War have obviously contributed to the enhancement of both overt and covert political techniques.

Until 2014, the extent of Russia’s active measures in the West – perhaps with the exception of the Baltic states – was limited. Russian authorities preferred to use their personal contacts with Western leaders and economic cooperation to advance their interests in the West. Given the domination of postmodern Realpolitik in the West, the Kremlin was largely successful in its endeavours, while Putin’s apparently friendly relations with Silvio Berlusconi (Prime Minister of Italy in 1994–1995, 2001–2006 and 2008–2011), Gerhard Schröder (Chancellor of Germany in 1998–2005) and, to a lesser extent, Nicolas Sarkozy (President of France in 2007–2012) allowed Moscow and Western capitals to ‘smooth away’ their differences to the disadvantage of human rights and political freedoms in Russia, as well as national security of the countries in the ‘near abroad’. In 2009, even the Obama administration, following the Russian invasion of Georgia, attempted to improve relations with Russia with the help of a so-called ‘reset’, although it did not collaborate as closely.

After Russia had occupied and then annexed Ukraine’s Autonomous Republic of Crimea and invaded Eastern Ukraine in 2014, some Western leaders belatedly realised – often without admitting their own complacency – that Putin’s regime became too assertive and defiant, as well as directly threatening European security and challenging the post-war order. Russia was suspended from the PACE and G8, while the EU, United States, Canada, Norway, Switzerland and some other nations imposed political and economic sanctions on Russia and its officials over the aggression against Ukraine.

Not only did Moscow respond with anti-Western sanctions, but also Russian state-controlled structures as well as groups loyal to the Kremlin dramatically stepped up active measures and other subversive activities inside the West. According to a report by the Chatham House, Putin’s Russia has used ‘a wide range of hostile measures’ including ‘energy cut-offs and trade embargoes, . . . subversive use of Russian minorities, malicious cyber activity of various forms, and the co-option of business and political elites’. A report by the Center for European Policy and Analysis argues that, in the West, the Kremlin ‘promotes conspiratorial discourse and uses disinformation to pollute the information space, increase polarization and undermine democratic debate. Russia’s actions accelerate the declining confidence in international alliances and organizations, public institutions and mainstream media’. Moreover, Russia ‘exploits ethnic, linguistic, regional, social and historical tensions, and promotes anti-systemic causes, extending their reach and giving them a spurious appearance of legitimacy’.

To a certain extent, today’s cooperation between various Russian pro-Kremlin actors and Western far-right politicians may be seen as an integral part of Moscow’s active measures in the West. However, it seems to be oversimplification to limit the relations between Russia and the Western far right to the Kremlin’s active measures, at least because such an assumption would reduce the agency of the other major element of this relationship, namely the far right itself.

European far-right milieu

The term ‘far right’ is used here as an umbrella term that refers to a broad range of ideologues, groups, movements and political parties to the right of the centre right. It is probably impossible to define an umbrella term such as ‘far right’ as anything less vague than a range of political ideas that imbue a nation (interpreted in various ways) with a value that surpasses the value of human rights and fundamental freedoms. Thus, the concept of a nation is central to all manifestations of the far right, but they differ in the ways they imagine the ‘handling’ of a nation.

The exponents of fascism, which was the very first far-right ideology to have acquired worldwide significance, offered arguably the most radical approach to ‘handling’ a nation. According to Roger Griffin, fascism can be defined as

a revolutionary species of political modernism originating in the early twentieth century whose mission is to combat the allegedly degenerative forces of contemporary history (decadence) by bringing about an alternative modernity and temporality (a ‘new order’ and a ‘new era’) based on the rebirth, or palingenesis, of the nation. Fascists conceive the nation as an organism shaped by historic, cultural, and in some cases, ethnic and hereditary factors, a mythic construct incompatible with liberal, conservative, and communist theories of society. The health of this organism they see undermined as much by the principles of institutional and cultural pluralism, individualism, and globalized consumerism promoted by liberal ism as by the global regime of social justice and human equality identified by socialism in theory as the ultimate goal of history, or by the conservative defence of ‘tradition’.

In the two twentieth-century European regimes, which successfully implemented essential tenets of fascism on the state level, namely Benito Mussolini’s Italy and Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, fascisms differed largely in that Italian Fascists conceived the nation in ethnic terms, while the German National Socialists articulated their idea of the nation in racial terms, or to be more precise, in terms of the Volk, a metaphysical notion incorporating the concepts of race, German history and culture. The difference in these interpretations of the nation as the core concept for the definition of fascism allows for distinguishing a very specific form of fascism, namely National Socialism or Nazism, that emphasises a specifically racist or völkische interpretation of one’s own nation.

After the military defeat of the Third Reich in 1945, fascism was forced to evolve into three major forms. Organisations that still wanted to participate in the political process had to dampen their revolutionary ardour rather dramatically and translate it ‘as far as possible into the language of liberal democracy’. This strategy gave birth to the non-fascist phenomenon of radical right-wing political parties. Revolutionary ultranationalists, on the other hand, retreated to the fringes of sociopolitical life in the West. As they still remained true to the idea of an alternative totalitarian modernity underpinned by the palingenesis of the nation – however unrealistic its implementation was in the post-war period – their ideas and doctrines were termed as neo-fascist (but sometimes simply fascist) or neo-Nazi. The third form of post-war fascism appeared only at the end of the 1960s and was associated, first, with the French New Right (or Nouvelle Droite) and, later, with the European New Right. This is a movement that consists of clusters of think-tanks, conferences, journals, institutes and publishing houses that try to modify the dominant liberal-democratic political culture and make it more susceptible to a nondemocratic mode of politics. Importantly, the European New Right has focused almost exclusively on the battle for hearts and minds rather than for immediate political power. As biological racism became totally discredited in the post-war period, the European New Right came up with the idea of ethno-pluralism arguing that peoples differed not in biological or ethnic terms but rather in terms of culture. Naturally, the above-mentioned forms of the far right thought need to be treated as ‘ideal types’ in the Weberian sense of the term. The boundaries between them are often blurred, while their various permutations – including those adopting elements of other, non-nationalist ideologies – embodied in the plethora of groups, movements and organisations have acquired new names such as national-revolutionary and national anarchist movements, racial separatism, Radical Traditionalism, national communism, Identitarian Movement, Third Position, neo-Eurasianism, etc.

Radical right-wing political parties are arguably the most widespread form of far-right politics today. Michael Minkenberg defines right-wing radicalism as ‘a political ideology, whose core element is a myth of a homogeneous nation, a romantic and populist ultranationalism directed against the concept of liberal and pluralistic democracy and its underlying principles of individualism and universalism’. He argues that ‘the nationalistic myth’ of right-wing radicalism ‘is characterized by the effort to construct an idea of nation and national belonging by radicalizing ethnic, religious, cultural, and political criteria of exclusion and to condense the idea of nation into an image of extreme collective homogeneity’.

Cas Mudde provides yet another insightful interpretation of what he calls ‘radical right-wing populism’ suggesting that it can be defined as a ‘combination of three core ideological features: nativism, authoritarianism, and populism’. As Mudde argues, nativism ‘holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (“the nation”) and that non-native elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state’; authoritarianism implies ‘the belief in a strictly ordered society, in which infringements of authority are to be punished severely’; and populism ‘is understood as a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”’.

There is less academic consensus on the differences between the radical right and the extreme right, and, for example, French and German scholars of far-right politics use the terms like droite radicale or Rechtsradikalismus less often than the terms extrême droite or Rechtsextremismus when they refer to the political phenomena that, especially in the Anglo-Saxon academic world, would generally be distinguished between right-wing radicalism (or radical right-wing populism) and right-wing extremism. In this book, this distinction exists and implies that the difference between radical right-wing and extreme right-wing movements and parties is their attitude towards violence as an instrument of achieving political goals: the former reject it, while the latter tolerate or even embrace it.

The blurring of the boundaries between various forms of far-right politics is also reflected in the ideological heterogeneity of the electorally most successful far-right parties of today, namely the radical right-wing populist parties. Many of these parties have long political histories, and, over the years, they have integrated many activists coming from the movements and organisations of varying degrees of radicalism or extremism. Activists who have fascist, neo-Nazi or extreme-right background may and usually do moderate under the pressure of the party leadership who – for political or tactical reasons – believe that extremist ideas and rhetoric will be harmful for electoral success.

Indeed, the deradicalisation process has become a common stage for the most successful European far-right parties today. The Norwegian Fremskrittspartiet (Progress Party), which was considered a radical right-wing party in the past, has gradually removed or toned down most of its hardliners and now perhaps cannot be even considered a far-right party anymore. In the European Parliament, the Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People’s Party) and Perussuomalaiset (The Finns) prefer to cooperate with conservative parties such as the UK’s Conservative Party and Poland’s Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice), rather than with the radical right-wing populists represented, for example, by France’s Front National (National Front, FN), Austria’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (Freedom Party of Austria, FPÖ) or Italy’s Lega Nord (Northern League, LN). However, the FN, FPÖ and LN have taken steps to moderate too. Under the leadership of Marine Le Pen, the FN even expelled her father and the FN’s long-time President Jean-Marie Le Pen for his radicalism. In the recent years, Hungary’s radical right-wing Jobbik party, too, has considerably toned down its anti-Semitic and anti-Roma rhetoric, and the deradicalisation strategy has proved to be relatively successful: at the time of the writing, Jobbik is the second most popular party in Hungary.

There is a historical precedent for this process: the most notable early example of deradicalisation of the far-right is the refashioning of the fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement) into a ‘post-fascist’ party in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This was followed by the expulsion of right-wing extremists and transformation into the national-conservative Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) in 1995, and, eventually, the merger of the Alleanza Nazionale into Silvio Berlusconi’s now defunct centre-right Popolo della Libertà (People of Freedom) in 2009.

Deradicalisation has contributed to the growing popular support for the ‘moderated’ radical right-wing parties, allowing them to enter sectors of the political spectrum that mainstream parties have long abandoned. Compared to the 1990s, the ‘moderate’ radical right now have even more appeal to liberal voters concerned about identity issues, to the working class on labour and immigration issues, and to conservative voters anxious to preserve so-called traditional values.

Doubtlessly, deradicalisation is not a mandatory condition for the electoral success of the far right, which is corroborated by the electoral fortunes of the Greek neo-Nazi Laïkós Sýndesmos – Chrysí Avgí (Popular Association – Golden Dawn, XA) at the parliamentary elections in 2015 or the Slovak extreme-right Kotleba – Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko (Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia) at the parliamentary elections in 2016. However, in general, the more extreme the far-right parties are, the less electoral support they have, and vice versa. Some of the more extreme far-right parties of today, for example, the British National Party (BNP), Italian Forza Nuova (New Force), Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (National-Democratic Party of Germany, NPD) or Svenskarnas parti (Party of the Swedes) have rarely had any tangible electoral successes. Even if many citizens of Western countries are seeking existential refuge in national identities, they are predominantly repulsed by blatant right-wing extremism and racist rhetoric. Some elements of the electorate of radical right-wing populist parties may clearly be driven by more extreme views than those espoused by their political favourites, but the majority of the voters do not seem to be racists or ultranationalists. Elaborating on the observation made by Laurent Fabius, France’s Socialist Prime Minister (1984–1986), who said in 1984 that the FN’s Jean-Marie Le Pen asked the right questions but came up with the wrong answers, one can suggest that the greater part of the electorate of radical right-wing parties make their electoral decisions because they are tempted by the right questions that the more moderate far-right politicians ask – about the efficiency of the liberal-democratic establishment, economic inequalities, job security, social cohesion, immigration, religious traditions and identity. Not that the far right give smart answers, but their defiant readiness to pose questions, some of which very few mainstream politicians would dare to address or even ask, bolsters their support.

The more support the radical right-wing populists have, the more opportunities they have to promote their visions and utopias in the socio-political environment in which political postmodernists are crushing despondent liberal progressivists, while disgruntled Western citizens are increasingly disaffected with the mainstream political class as a whole.

Research background

Until 2014, apart from occasional references to pro-Russian statements of some European far-right leaders, few scholars and experts observed a growing rapprochement between the Western far right and Putin’s Russia. Arguably the first investigation that reported on this development was a report titled ‘Russia’s Far-Right Friends’ and published in 2009 by the Hungary-based Political Capital Institute. On the basis of their research, its authors argued that ‘far-right parties in several eastern European countries [had] become prominent supporters of Russian interests and admirers of the Russian political-economic model’ and that, for Russia, ‘forming partnerships with ultranationalists could facilitate its efforts to influence these countries’ domestic politics . . . until Moscow finds an even more influential ally elsewhere on the political spectrum’.

In 2010, Angelos-Stylianos Chryssogelos analysed the foreign policy positions of the radical right-wing FN and FPÖ, as well as of the German left-wing populist Die Linke (The Left), and specifically focused on their attitudes towards the United States, transatlantic relations, NATO and Russia. He concluded that these parties were united in their aversion of NATO and American influence in Europe, but, at the same time, they looked favourably at Putin’s Russia. According to Chryssogelos, ‘populist parties see Russia as a source of energy and military clout as well as an attractive partner with similar cultural traits as Europe has’, while by discarding ‘issues of human rights and democracy in their relations with Russia’, these ‘populists reinforce their vision of sovereign nation states furthering their interests without reference to universal values or prior institutional commitments’. The author, however, did not elaborate on the Russian agenda behind the cooperation with the European far right.

The international expert and academic community in general started to pay attention to the relations between Russia and the Western far right in 2013–2014. For example, Marcel Van Herpen noted that West European far-right parties were moving away from ‘their traditional anti-communist and anti-Russia ideologies, with many expressing admiration – and even outright support’ – for Putin’s regime. Van Herpen asserted that, since Putin’s regime did not ‘openly reject democracy or explicitly advocate a one-party state’, it might serve as a model for the far-right parties, which could not ‘openly advocate an authoritarian regime or a one-party system’. Moreover, through its specific policies and practices, Putin’s regime was able to demonstrate to the illiberal European political forces ‘how to manipulate the rules of parliamentary democracy . . . to serve authoritarian objectives’.

The Political Capital Institute continued working on the phenomenon of ‘Russian influence in the affairs of the far right’ seen as ‘a key risk for Euro-Atlantic integration at both the national and the [European] Union level’. The Institute’s 2014 report distinguished – in the context of their views on Russia – between ‘committed’, ‘open’ and ‘hostile’ European far-right parties. The ‘committed’ category would include parties that openly professed their sympathy for Russia. The ‘open’ category would refer to parties that could either ‘show sympathy based simply on considerations in relation to foreign and economic policy and realpolitik, without regard to Putin’s economic and social regime as a model’, or ‘in most cases display a negative or neutral attitude toward Russia’, but at the same time would ‘support the Russian position [on some important issues] even in the absence of genuine motivation’. Finally, the ‘hostile’ category would include far-right parties coming ‘primarily from countries in conflict with Russia’. In 2015, the Political Capital Institute also published four collaborative country-specific reports on the relations between various Russian stakeholders and the far right in Hungary, Greece, France and Slovakia. Marlène Laruelle, who co-authored the France-related report, edited an insightful collection of chapters that looked at the relations between Russia and the far right through the perspective of the spread of the ideology of Russian neo-Eurasianism, as well as focusing, in particular, on the cases of France, Italy, Spain, Hungary and Greece.

Aims and structure of the book

Despite the rising number of journalistic investigations, expert analyses and academic studies of the phenomenon, we still lack a general picture of the relations between Russia and the Western far right, and this book is set to address considerable gaps in our understanding of this under-researched yet important aspect of international relations.

Relations between Russia and the Western far right are a complex and multi-layered phenomenon which cannot be explained by any single causal factor. The overarching hypothesis of this book is that each side of this relationship is driven by evolving and, at times, circumstantial political and pragmatic considerations that involve, on the one hand, the need to attain or restore declining or deficient domestic and international legitimacy and, on the other hand, the ambition to reshape the apparently hostile domestic and international environments in accordance with one’s own interests. Putin’s corrupt and authoritarian regime enjoyed, especially during his first presidential term (2000–2004) domestic and international legitimacy, but started to feel increasingly threatened by the processes of democratisation in Russia’s immediate neighbourhood as it perceived these processes as a Western attempt to bring about a regime change in Russia. These assumptions on the part of the Russian ruling elites led to their gradual opening to Western far-right politicians who had tried to court Putin’s regime even before Russian pro-Kremlin actors decided to turn to them to use them, first, as one of the sources of political legitimacy in the domestic environment and, thus, consolidation of the regime, then as tools of Moscow’s foreign policy in the Russian neighbourhood, and, eventually, as an instrument of destabilisation of Western societies. In the latter case, Moscow’s intentions are, to a certain degree, underpinned by the understanding that the far right are more potent today than they have ever been before in the post-war era and are posing a growing threat to Western liberal democracy. Moreover, radical right-wing parties no longer need to vindicate themselves and be at pains over proving political eligibility of their ideas. Today, they refer to Putin’s Russia as the model of an alternative political order opposing liberal democracy. By expressing their ideological kinship with contemporary Russia, which is far from being a fringe country, and winning different forms of support from Moscow, radical right-wing parties may claim alternative political legitimacy and represent themselves not simply as the opposition to the mainstream parties, but essentially as the alternative mainstream.

This book aims to explore relations between various Russian actors and the far right in all their complexity by scrutinising their most important aspects. The fact that some initial analyses of the pro-Russian sentiments of the contemporary Western far right started to appear only in 2009–2010 does not imply that these sentiments did not exist before, and it is almost impossible to understand them without examining their nature and historical manifestations. Thus, Chapter 1 goes back as far as the interwar period to show that, even then, particular elements of the far right sided with Russia, and then explores how the far-right pro-Russian attitudes developed in the West during the Cold War, as well as pointing out that Soviet Russia was often prone to use the Western far right for its own political benefits. Chapter 2 discusses the active cooperation, as well as the motivations behind this cooperation, between Russian and Western far-right politicians after the fall of the Soviet Union; while their attempts at building more structured relationships largely failed at that time, they facilitated and contributed to the deepening of the relations between Russian pro-Kremlin actors and the Western far right when more favourable conditions arose in the second half of the 2000s. The emergence of these conditions was determined by the internal evolution of Putin’s regime from an authoritarian kleptocracy into an anti-Western right-wing authoritarian kleptocracy in the second half of the 2000s, and Chapter 3 discusses this evolution and demonstrates how particular elements of the Western far right embraced it. Chapters 4 and 5 consider two areas of dynamic cooperation between various Russian actors and Western far-right politicians and organisations aimed at supporting and consolidating alternative institutions that aspire to challenge and undermine liberal-democratic practices and traditions: electoral monitoring and the media. Chapter 6 looks at openly pro-Russian activities that European far-right movements and organisations have carried out in their national contexts, and identifies several types of structures and individuals who furthered cooperation between the European far right and the Russian actors linked to the Kremlin. Finally, Chapter 6 explores the performance of European far-right politicians on high-profile discussion platforms in Moscow and at sessions of the European Parliament in Strasbourg and Brussels, and analyses the narratives that they promote within these settings.

This book not only aims to provide deeper insights into the cooperation between Putin’s Russia and representatives of the Western far right, but will also inspire further, more narrow research into this phenomenon and its particular aspects. The urgency of these endeavours cannot be overstated. The Western liberal-democratic order, being challenged by destructive developments from outside and inside Western societies themselves, faces hard times. The Western world, to be sure, is strong enough to resist the challenges of either the far right or Putin’s regime. Individually, neither of these forces can bring about the collapse of the West as we know it. But we witness today that Putin’s Russia gradually joins forces with the far right against liberal democracy; they reinforce each other, and their coalition may be able to weaken and destabilise the West and, especially, the EU.