The on-again, off-again flirtation between Mother Russia and the deplorables of Europe

Jay Kinney

A central accusation in the uproar over “Russian influence” holds that Moscow is covertly in cahoots with the American alt-right, supplying the movement with fake news, memes, and social media talking points. The evidence for this tends to be more speculative than solid, but the general question of post-Soviet Russia’s cooperation with Western nationalist and racialist groups is certainly salient.

A central accusation in the uproar over “Russian influence” holds that Moscow is covertly in cahoots with the American alt-right, supplying the movement with fake news, memes, and social media talking points. The evidence for this tends to be more speculative than solid, but the general question of post-Soviet Russia’s cooperation with Western nationalist and racialist groups is certainly salient.

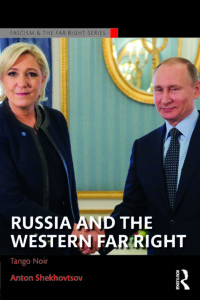

Such links are at the heart of Anton Shekhovtsov’s new study, Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir. Shekhovtsov is a fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, and his book is exhaustively detailed in its description of Russian relations with the European far right. What impact this may have had on the American right comes up only in the book’s final three paragraphs, which mostly raise questions and provide no answers.

Shekhovtsov argues that a range of reactionary groups, largely in Europe, see Putin “as an ally in their struggle against Western liberal democracy and multiculturalism.” Moscow, in turn, uses them both “to consolidate the authoritarian kleptocratic regime at home” and “to counteract the growing isolation of Russia in the Europeanised world.” And in some cases, the author argues, Russia wants “to disrupt the liberal-democratic consensus in Western societies and, thus, destabilize them.”

Shekhovtsov begins his survey with an early precedent. In the 1920s, the Soviet Union explored possible cooperation with the Western far right. While this never amounted to much, it did coincide with the emergence in Weimar Germany of an ideology of “National Bolshevism” among fringe-left German nationalists. This tendency saw a later revival of sorts among Russian far-right groupuscules in the 1990s.

During the Cold War, the Soviets sometimes found it useful to provide covert support to far-right actors as a means to stir up trouble for Western liberal democracies. For example, Soviet and East German intelligence agencies funneled funds to former Nazis and other radical rightists in West Germany because they were proponents of German neutrality. One such client was Rudolf Steidl, who received 2,363,000 Deutschmarks during 1951–1954 to publish the Deutsche National-Zeitung propaganda newspaper.

Another campaign, in 1959–1960, involved KGB agents in West Germany who went on a spree “painting swastikas and anti-Semitic slogans on synagogues, tombstones, and Jewish-owned shops.” The intent was to give a black eye to West Germany and “produce a snowball effect where troublemakers would carry out anti-Semitic activities on their own.” As Shekhovtsov notes, the operation “helped East Germany legitimise itself as a peace loving, antifascist state” by comparison.

In Austria in the early ’50s, while the Soviets and the Western forces both occupied sectors in Vienna, the Soviets helped support the National League, a far-right movement partly composed of former Nazis. Its newspaper, Österreichische National-Zeitung, also promoted neutralism.

You might think such alliances would be ideologically taboo, but counterintelligence can make for strange bedfellows. This cuts both ways, as when the CIA supported Islamist militias fighting the USSR in Afghanistan in the ’80s. As the venerable aphorism goes, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”—at least until the blowback hits.

This does not mean that Russian contacts with Western far-right groups and individuals have always been part of a coherent, top-down governmental strategy. Shekhovtsov notes that initial contacts in the Yeltsin era were largely between far-right leaders of small Russian political parties and their counterparts in Western Europe.

Thus, Aleksandr Dugin, while a leading Russian intellectual proponent of Eurasianism in the 1990s, met Alain de Benoist and Robert Steuckers, two significant theorists of the French and Belgian New Right, respectively. Dugin invited them to participate in a panel discussion held in the office of a far-right Russian newspaper.

Similarly, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia—despite its name, a far-right group—met with Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the French National Front, and with “multi-millionaire media czar” Gerhard Frey, founder of the German People’s Union. In this instance, support flowed from West to East, in the form of financial support from Frey and donations of some computers and a fax machine from the National Front.

Sergey Glazyev, a member of the Russian Duma, forged links with Lyndon LaRouche, inviting the well-known American crank to disseminate his conspiracy theories to an audience in Moscow. (LaRouche’s Schiller Institute already had a Russian branch, so this was not purely Glazyev’s initiative.)

It may be hard to remember now, but many Western politicians and analysts initially saw Putin as a reformer who could normalize Russia’s economy. And some reform did occur. But in due course, national leadership was reconcentrated among the siloviki—that is, members of the various intelligence and security agencies. Their presence in the Russian ruling elite rose from 17 percent under Boris Yeltsin to 31 percent under Putin as of 2008.

Shekhovtsov’s book portrays Russia’s putative democracy as a Potemkin village going through the formalities of elections, a parliament, mass media, and a civil society, all of which have been hollowed out by the siloviki’s permanent hold on power. (You could even call them a “deep state.”) Opponents have been eliminated or defanged, while Putin has appealed to Russian nationalism and conservative Orthodox culture and traditions in rallying popular support for his regime.

Stung by the “color revolutions” in some former Soviet republics—revolts he attributed to Western interference—Putin felt the need to counter poll watchers from the European Union (who commonly pointed out irregularities in elections and referendums in former Soviet states) with sympathetic poll watchers drawn from the European far right. The ground for such collaboration was laid when Moscow sought out Western groups who shared a skepticism of the European Union and an opposition to NATO.

If Putin seemed uninterested in the Western far right during his first term as president (2001–04), this began to change in the latter half of the decade, as he felt increasingly isolated from mainstream Western respect. The underlying drive, Shekhovtsov argues, is Putin’s determination to maintain power. He’ll pursue pragmatic alliances with mainstream European centrist parties if they’re willing, and go with far-right factions when they seem like the best bet. If that means flirting with François Fillon’s center-right party in France, so be it. If that attempt fails, Russian gestures toward the French National Front will be the next best choice. Russia can roll with the punches and side with whichever political camp might be ahead in the polls. Self-preservation comes before ideology.

Much of Russia and the Western Far Right is taken up with identifying and tracing Russia’s interaction with Western rightists. But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the latter are almost all marginal figures trying to leverage these dealings to burnish their own reputations. The book’s cover photo shows Marine Le Pen of the French National Front shaking hands with Putin, but very few on the far right make it that far. More commonly, fringe players, such as André Chanclu, a French far-right activist and founder of the France-Russia Collective, are invited to Russian think-tank symposiums and given photo ops with second- or third-level bureaucrats. Their egos are stroked, a bit of funding may flow their way, but it’s all rather small potatoes.

As valuable as Shekhovtsov’s research may be, it is complicated for non-academic readers by a proliferation of political labels, among them “far right,” “extreme right,” “neo-Nazi,” “fascist,” and “populist,” which tend to overlap and sometimes seem to lose their distinctions. One is reminded of Hillary Clinton’s famous “basket of deplorables” speech, which effectively merged all sorts of disparate Trump supporters into a semantic catchall amounting to “the bad guys.”

That said, this is a work of serious scholarship on a tangled subject. And while its subjects are mostly European, it’s clearly relevant to Americans too, particularly as politicians and the press try to decipher (or obscure) Russian activities during our elections.

Shekhovtsov suggests the U.S. alt-right would be a fruitful milieu for further research, but aside from trotting out the names of Steve Bannon and Richard Spencer—the latter was recruited in 2013 as an occasional commentator for the Russian TV channel RT—Shekhovtsov has nothing to add. I suspect this reference was inserted at the publisher’s request to inject a semblance of current pertinence into a book largely completed before the 2016 election season.

Perhaps Russian agents were up to their elbows in hacking emails and spreading mischievous disinformation during the campaign; perhaps their operations amounted to little more than some Pepe the Frog meme trolling online. Either way, Russia and the Western Far Right offers essential background.